Introduction

I’ll never forget the first time I heard the chilling details of the Tenerife airport disaster. Two planes, a KLM and a Pan Am, collided on the runway, killing 583 people. It was a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of organizational accidents. That event, and countless others, sparked a fascination with aviation safety that led me to James Reason’s “Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents.” This book offers a profound organizational perspective on accident causation, and in this article, I’ll share three key concepts that have significantly shaped my understanding of safety.

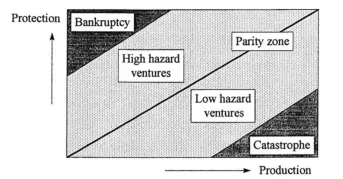

James Reason's production-protection graph

James Reason states that an organization ( an airline, in our case) must give enough attention to both production and protection. Production is all about operating flights and maximizing profits so the business can flourish. After all, that is the main goal. Besides, there are employees to pay ! So production is very important for an airline.

On the other hand, there lies protection. It is all about strictly following rules, regulations and internal procedures to ensure flight safety. Protection is just as important as production, given the economic downfall that an accident may cause.

According to James Reason, a company must find the equilibrium between both production and protection. In fact, not focusing enough on production can lead to bankruptcy. In the same way, focusing too little on protection can lead to a catastrophe (accident), which is even more delicate as it may cause both loss of lives and bankruptcy.

The graph below clearly illustrate what we just discussed.

The vulnerability of installation

In his book, James Reason made the following assertions and provided evidence for each one of them:

- Of the three kinds of human activity that are universal in hazardous technologies — control under normal conditions, control under emergency conditions and maintenance-related activities-the latter poses the largest human factors problem.

- Of the two main elements of maintenance-the disassembly of components and their subsequent reassembly-the latter attracts by far the largest number of errors.

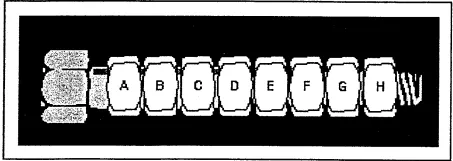

The latter can be experimentally proved by taking a look at the figure below.

Let us consider this bolt with its eight nuts. There is just one way to dissassemble it correctly which is by removing respectively the nuts, from H to A. However, when it comes to reassembly, there are 40000 (factorial 8) to do so ! Hence, the odds of assemblying them in the wrong order are very high. Besides, it is also easy to omit one nut in the assembly process. James Reason captures this concept beautifully:

The problem of omission according to James Reason

Now that we’ve established that installation (assembly )is the element of maintenance that is more likely to attract more human factor problems, let’s us talk about the most frequent error type in maintenance assembly : omission. James Reason defined omission as the the failure to carry out necessary steps in the task.

After providing enough data to prove his claim, James Reason — and that’s my favourite part — proceeded to explain that there are certain characteristics in a task that make it omission prone. Here are a few examples of those charcteristics:

- Steps involving actions or items not required in other very similar tasks.

- Steps involving recently introduced changes to previous practice

- Steps involving recursions of previous actions, depending upon local conditions.

- Steps involving the installation of multiple items (for example, fastenings, bushes, washes, spacers and so on.)

- Steps that are dependent upon some former action, condition or state

Conclusion

This book has been instrumental in shaping my understanding of aviation safety, even leading me to pursue a graduation project focused on accident and incident prevention through data analysis. James Reason’s insights, particularly regarding the production-protection balance and the vulnerabilities inherent in maintenance tasks, offer crucial lessons for anyone involved in high-risk industries. Understanding these concepts is the first step towards building a safer future for aviation.